Human capital, the tree of golden but neglected apples: The Portuguese case within OECD countries

Human capital is intangible and hard to define bringing many difficulties to a consensual definition but health and education are regularly used to quantify its value.

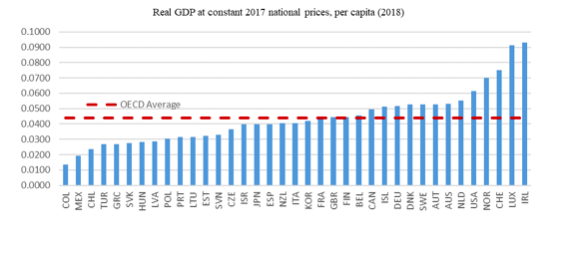

Portugal has a growing tree with golden apples but these keep falling into neighbor’s yard. This is the main conclusion when analyzing some indicators related to characteristics of Portuguese students (and future workers). For a long time, economists have highlighted human capital as one of the essential determinants of economic growth with benefits that are not exclusively for economic aspects, there are also non-economic gains for health, well-being and social robustness. Data seem to indicate that Portugal has not neglected this principle. However, if this is true, why is Portugal persistently below OECD average when we look at national income?

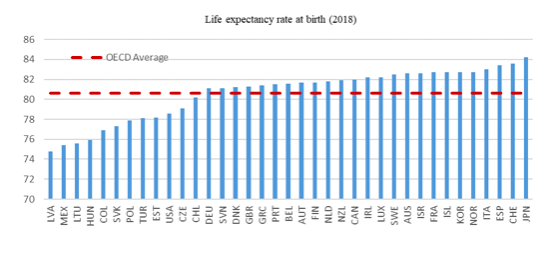

Human capital is intangible and hard to define bringing many difficulties to a consensual definition but health and education are regularly used to quantify its value. Health has its importance for measuring human capital as healthier populations tend to be more productive since they have the necessary conditions for thinking better, missing less days of work or school, more focus and more incentives for investing on education/instruction. A common proxy for measuring national health is life expectancy; data reveals a good positioning of Portugal with a value around median.

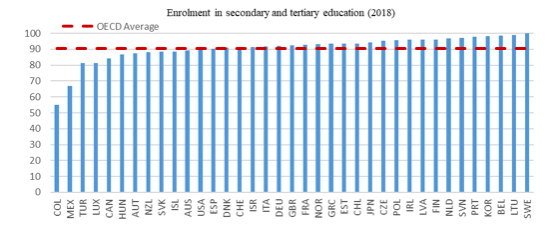

The idea of using education, as a proxy for human capital, relies on considering more educated individuals tend to be more skilled, more productive and facilitates the generation of new ideas and processes. When analyzing enrolments rates for Portugal within OECD countries it is possible to verify that, not only is above average but also stands at the top five countries.

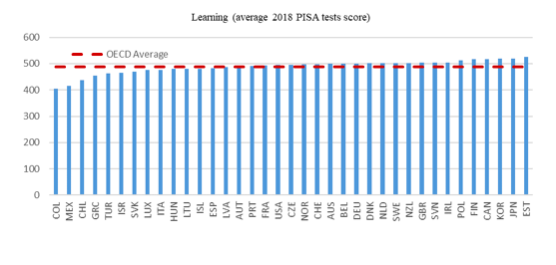

Some may insist on the fact that more enrolment does not necessarily means more learning and this may be a reasonable statement. The Programme for International Student Assessment (known as PISA) announced their last report at 2018 and Portugal scored an average value of 492 that is just near, but above, the OECD average.

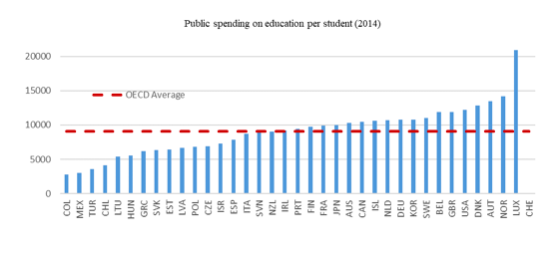

The mentioned figures may point to some recognition for the Portuguese students’ accomplishments but, when looking at data for public spending on education, this acknowledgement should be shared with the Portuguese government.

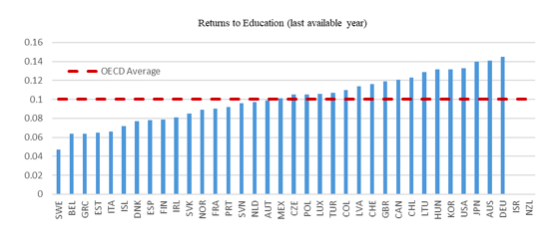

When the vision switches into the labor market, several issues come up. Allied to the fact that unemployment rates for the youngest are persistently around 20%, there is also a trend to undervalue workers as the estimated returns to education are below the average of OECD countries. These may be some of the reasons for emigration!

An overview through data made me realize that there is a good performance for Portugal when it comes to assess its human capital at training. Portuguese governments seem to do an effort to provide some conditions to students with an above the OECD average spending on education and this may be one of the many drivers for students’ success. In spite of the mentioned success, it is worth to mention that most of the indicators are slightly around the average, meaning that Portugal is still far away from top performers. On the other hand, labor market is nowadays the Portuguese greatest barrier for economic performance; it does not value its greatest asset (human capital) neglecting all its potential and wasting all the public investment made.

So, why is Portugal persistently below OECD average when we look at national income? In my opinion, it is mostly because Portugal cannot retain human capital at the exact moment when it could bring some gains to the economy. There is a global effort for generating a robust human capital then it does not seem that state is failing in an initial moment. What it seems to be the crucial point here is that labor market neglects what it could be its “golden apples” due to the outdated idea that young workers do not add value to firms, summing up the fact of the inflexibility of the Portuguese market. Therefore, our “apples” do not have alternative but to emigrate, “falling into neighbor’s yard.”

Notes:

- All figures, except “Returns to Education”, are generated using data obtained from OECD website;

- Returns to education were estimated by Montenegro and Patrinos (2014);

- All figures tried to range the most OECD countries possible forcing, sometimes, a switch on the year of analysis (presented between parentheses).

- Caption for country abbreviations: AUS – Australia; AUT – Austria; BEL – Belgium; CAN – Canada; CHL – Chile; COL – Colombia; CZE – Czech Republic; DNK – Denmark; EST – Estonia; FIN – Finland; FRA – France; DEU – Germany; GRC – Greece; HUN – Hungary; ISL – Iceland; IRL – Ireland; ISR – Israel; ITA – Italy; JPN – Japan; KOR – Korea, Rep.; LVA – Latvia; LTU – Lithuania; LUX – Luxembourg; MEX – Mexico; NLD – Netherlands; NZL – New Zealand; NOR – Norway; POL – Poland; PRT – Portugal; SVK – Slovak Republic; SVN – Slovenia; ESP – Spain; SWE – Sweden; CHE – Switzerland; TUR – Turkey; GBR – United Kingdom; USA – United States.

Bibliography:

OECD (2021) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Website. Accessed on: https://data.oecd.org/.

Montenegro, Claudio & Harry Patrinos (2014) Comparable Estimates of Returns to Schooling around the World. Policy Research Working Paper 7020, World Bank Group.