EU/Presidency: Portuguese term ends without visible economic recovery

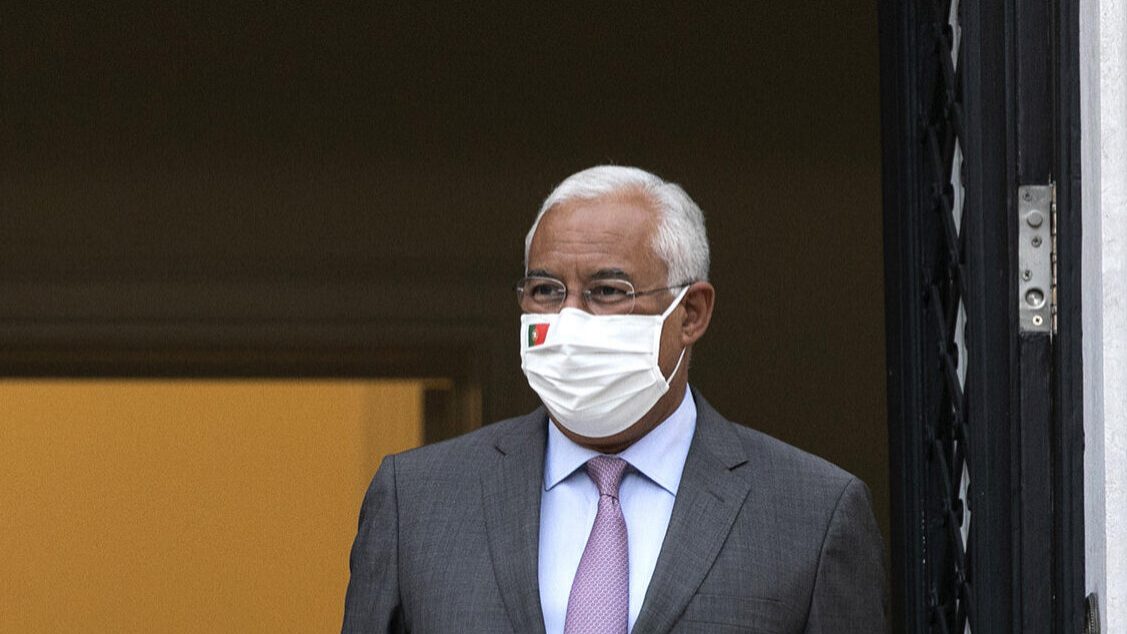

"It was time to act, and we have acted," prime minister António Costa said last week as he reviewed Portugal's fourth EU presidency before his counterparts.

The efforts were considerable. Still, the Portuguese presidency of the Council of the European Union ends this Wednesday without achieving one of its major goals: to see the post-Covid-19 pandemic economic recovery be implemented on the ground.

“It was time to act, and we have acted,” prime minister António Costa said last week as he reviewed Portugal’s fourth EU presidency before his counterparts.

The goal of having national plans approved by June 30, paving the way for the release of the first ‘tranche’ of the Recovery and Resilience Fund, was announced as early as December by the foreign minister, Augusto Santos Silva, and renewed in April, when António Costa pointed to the approval of a first package of Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRP) at the meeting of finance ministers (Ecofin) on June 13.

Portugal was the first country to present its investment plan to the European Commission formally. Still, other member states were not so quick: on April 30, the indicative deadline for submission, only eight of the 27 had done so, and today, two months later, there are still three countries that have not done so.

The Commission has since approved 12 plans, the same ones to be submitted to Ecofin on July 13, almost a year after the historic summit in which European leaders agreed to create a €750 billion fund to be financed, for the first time in EU history, with debt issued in the name of the 27.

In this other aspect, Portugal made the difference, never relaxing in its pressure on the remaining member states to ratify the decision on the so-called own resources.

This process was concluded on May 28, allowing the Commission to launch the first and largest ever issue of institutional bonds in the EU on June 15, raising €20 billion.

Still on the economic side, and having also set itself the goal of approving all the regulations for the entry into force of the multiannual financial framework, the EU budget for 2021-2027, the presidency negotiated and managed to get practically all the legislation approved, including the reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), agreed in the last few days.

Portugal had set as its third major objective to reach the end of June with the Covid-19 vaccination process “well advanced” in all member states, an “essential element for economic and social recovery”.

After significant delays in the first quarter, during which only 4.1% of the EU adult population was immunised, the reinforcement of vaccine delivery allowed progress. Still, inequalities between states are important, and the emergence of the Delta variant complicated and set back the easing of lockdown measures in several regions and countries.

A victory in this area was the Covid-19 digital certificate, adopted “in record time” to facilitate movement within the EU.

The Portuguese presidency defined its fourth major objective as “a definitive impetus” for the realisation of the European Pillar of Social Rights, promoting a Social Summit in Porto, which brought together decision-makers, social partners, and civil society.

With 24 of the 27 European leaders present, a record in times of pandemic, the Summit ended with a declaration, the “Porto Commitment”, establishing a governance model with quantified objectives for employment, training and the fight against poverty.

However, the Summit was marked by the issue of lifting vaccine patents, proposed two days earlier by the US president, Joe Biden.

If initial reactions in Europe seemed favourable, the debate among the 27 over dinner, which lasted four hours, ended with a majority against.

On the global level, the Portuguese presidency gave priority to the EU-India summit, which ended up being held with the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, at a distance, given the serious pandemic situation in his country. It ended with the relaunch of trade negotiations, suspended since 2013.

But the global aspect of the six-month period was marked above all by the reunion of Europe with the United States, the highlight of which was the summit of 14 June in Brussels, a transatlantic “reconciliation” brought about by the election of Biden.

In addition to major objectives, a presidency has several dossiers that carry over from the previous one, issues that drag on and unexpected developments.

This semester saw the approval of the Climate Law – which transposes the carbon neutrality into law until 2050 -, the directive on transparency for multinationals – which are now obliged to disclose where they make their profits and pay taxes – and the Children’s Guarantee – which will ensure access to essential services for 18 million children at risk or in poverty.

Some major deadlocks have been cleared, such as the one that delayed the start of the Future of Europe Conference for a year. Still, others, such as the new Migration Pact, have only seen technical developments, insufficient to envisage agreement soon, as Slovenia, which takes over the presidency on Thursday, has already admitted.

Others have not seen visible developments, such as the entry into force of the EU-Mercosur trade agreement or the launch of accession negotiations with Albania and Northern Macedonia.

On the other hand, despite Portugal’s insistence throughout the six months on the importance of defending the rule of law in the EU, which included the relaunch of proceedings against Hungary and Poland, the presidency ends with a controversy involving fundamental rights.

The “duty of neutrality” invoked by the secretary of state for European affairs in relation to a letter from 13 EU leaders defending European fundamental values, published after the approval in Hungary of a law prohibiting “the promotion” of homosexuality among under-18s, earned strong internal criticism from the government.

Initially planned for different scenarios of the pandemic’s evolution, the successive waves determined that the rule was often meetings by videoconference or hybrid, which affected the dynamics of some negotiations and, above all, the visibility of the presidency, with media coverage inevitably hampered.